Paper appears as: Slator,

Brian, et al (2001). Rushing Headlong into the Past: the Blackwood Simulation.

Proceedings of the Fifth IASTED International Conference on Internet and

Multimedia Systems and Applications (IMSA 2001). Honolulu, HI, August 13-16

Rushing

Headlong into the Past: the Blackwood Simulation

Brian M. Slator, Kerry

Wynne, David Burleigh, Josh Kadrmas, Elizabeth Kennedy, and the members of NDSU

CSCI 345: J.Alt, J.Aus,

D.Balliet, D.Balliet, C.Bergstrom, R.Blaha, K.Bopp, B.Carlson, S.Carlson,

G.Collins III, P.Crary, J.Cusey, M.Deck, A.Dewald, S.Dieken, A.Elezovic, D.Ely,

G.Engels, M.Ernst, K.Fimreite, E.Finke, C.Fredrickson, N.Fredrickson,

M.Guerard, T.Hall, M.Hanson, K.Hartman, W.Hawkinson, K.Hessinger, H.Ho,

J.Hoffert, J.Hoffert, C.Hofland, B.Hokanson, M.Holzer, M.Hoque, S.Hossain,

M.Hurlburt, B.Johnson, S.Kawamura, J.Levasseur, N.Lindvall, B.Lorentz,

J.Louwagie, D.Mafua, R.Martens, J.Matthews, B.Miller, S.Moorhouse, D.Olson,

K.Parisien, J.Reiser, C.Resler, J.Richardson, C.Romberg, S.Schilke, J.Schmidt,

D.Schott, S.Seira, R.Sell, B.Seymour, L.Sjoblom, J.Tarnowski, S.Ternes,

B.Thompson, T.Wells, M.Wolters, A.Wong,

Computer Science Dept., IACC Bldg. #258, North Dakota State University, Fargo, ND 58105

Abstract

The Blackwood Project is a

simulation of a mythical 19th Century Western river town.

Participants who join the simulation will accept or be assigned a role in the

simulation that is primarily economic in nature. In Blackwood, gameplay is

influenced by historical events and players are assigned roles designed to

promote collaboration and interaction. Players assume roles in the simulation,

such as a blacksmith, but are not expected to learn blacksmithing. Employee

software agents actually do the day-to-day chores. The players are “only”

expected to manage the retailing and business elements of the game. Continuing

the evolution and making improvements to the Blackwood Project are students in

various classes taught at North Dakota State University. These students assume

roles in a simulated consulting team in order to accomplish semester-length

goals improving one or more aspects of Blackwood.

Keywords: Distance Learning, Collaborative Learning, Educational Multimedia, Virtual Reality

Introduction

Computer-based education and distance learning systems

have become increasingly important facets of education, particularly in higher

education. These approaches to education are important not only for enhancing

the education of the traditional student, but they also hold the key for

expanding education to an enormous potential audience of non-traditional

students. Meanwhile, the value of “active” versus

“passive” learning has become increasingly clear (Reid, 1994). In

light of this, the Blackwood Project provides a computer-based educational

application for teaching fundamental, economic skills and knowledge, with an

emphasis on the marketing and administrative dimensions of the discipline. This

takes the form of an authentic, virtual environment where students are given

the means and the opportunity to undertake active role-based discovery and

learning.

Blackwood is periodically enhanced and improved upon

by a new crop of students in Computer Science courses. In order to take

advantage of the values of role-based learning, students in these classes act

out roles while simultaneously improving the Blackwood game itself.

Background

The Blackwood Project is a part of the research effort

of the NDSU Worldwide Web Instructional Committee (WWWIC; Slator et al., 1999).

It is the first attempt by this group at the “next generation” of

role-based virtual environments for education where the pedagogical simulation

will support cross-disciplinary content and choice of roles to promote player

interaction and potential collaborations. This next generation builds on

experience in designing and implementing the original ILS GAMES Project, the

NDSU Dollar Bay Retailing Game, and the NDSU Planet Oit Project. The goals of

the Blackwood Project include providing an engaging context for role-active

immersive distance education and a platform to teach business-oriented

problem-solving in a learn-by-doing pedagogical style (Duffy et al, 1983; Shute

and Glaser, 1990, Hill and Slator, 1998).

The WWWIC program for designing and developing

educational media attempts to implement a coherent strategy for all its

efforts: to deploy teaching systems that share critical assumptions and

technologies (e.g. LambdaMOO; Curtis 1997), in order to leverage from each

other's efforts. In particular, systems are designed to employ consistent elements

across disciplines and, as a consequence, foster the potential for intersecting

development plans and common tools for that development. Simulations are

implemented by building objects and interfaces onto a MOO ("MUD,

Object-Oriented", where MUD stands for "Multi-User Domain").

MUDs are typically text-based electronic meeting places where players build

societies and fantasy environments, and interact with each other. Technically,

a MUD is a networked multi-user database and messaging system. The basic

components are "rooms" with "exits", "containers"

and "players". MUDs support the object management and inter-player

messaging that is required for multi-player games, and at the same time provide

a programming language for writing the simulations and customizing the

environments.

Role-based

Environments

The theory of role-based environments is both simple

to explain and complex to implement. An apprentice watches their master,

learning techniques and practicing their craft; they observe the master's actions

and internalize them. When confronted with a problem, the apprentice asks,

"what would the master do in this situation?" And then the apprentice

models the expertise of the master in the pursuit of their goals. This is a

common experience shared by silversmiths, doctors, Ph.D. candidates, and anyone

else enculturating themselves into what they want to be. When John Houseman

says, in the Paper Chase that

"We are not teaching you the law, we are teaching you to think like a

lawyer," this is what he means. Similarly, there is little argument that

immersive foreign language learning is most effective; to learn French, go to

France. At some point, it is widely reported, you begin to “think in

French”, and that is what you want: acquisition of conceptual knowledge

in a meaningful problem-solving context.

The Game

The Blackwood game implements a mythical town, set in

the Old West (circa 1880), where players with Java-enabled browsers connect

across the Internet and “inherit” a virtual store. The game is

designed to impart the time-independent principles of microeconomics and the

practice of retailing, but within an historical context, and by promoting the

social and symbiotic relationships that sustain a business culture in the long

term. As each turn progresses, players learn their role in the environment and

see the results of their actions as well as the impact of other players’

actions within the constraints of the simulated world. Students learn about

culture (the ideas, values, and beliefs shared by members of a society) and

society (e.g., social structure and organization) while at the same time

developing historical cross-cultural awareness and understanding. And they will

do so in a role-based manner, immersed in an authentic context, assigned

authentic goals, and given the opportunity to learn to operate in an historical

context.

The Blackwood Project is hosted on the Internet and

provides a platform for opportunities for research into distance education,

intelligent agents, economic simulation, and assessment of pedagogical

approaches.

Following is a description of the game, as it existed

prior to January 2001. The implementation of the game had been created through

a collaborative effort of the WWWIC and student volunteers at NDSU.

Time

Frame

The simulation begins in the Spring of 1880 and

continues until the Great Flood destroys the town in the Spring of 1886. Since

each virtual week lasts about 8 clock hours, there are three virtual weeks in

each human day, and therefore the entire simulation takes approximately three

months.

The

Impact of History

Players of Blackwood “experience the

effects” of history. This is accomplished by the following mechanisms:

1.

Newspapers: The

simulation tracks events in the 1880-1886 time frame. As events happen in the

nation and around the world, they are reported in “Special

Editions”.

2.

Economic Trends: The

simulation reflects the impact of western expansion, the advance of railroads,

and the discovery of silver deposits, in terms of fluctuations in population.

This has immediate and discernible effects on player’s businesses as

demand (and prices) rise and fall.

3.

Atmosphere Agents: The

simulation supports a range of software agents that lend “color” to

the environment (buffalo hunters, fur trappers, street entertainers, and the

like)

The

Economic Simulation

An economic model was developed to generate consumer

behavior for the game (Hooker and Slator, 1996). The model takes as input the

decisions the players have made, and returns a level of demand for each of the

stores. In the game, players compete for market share against other human

players trying to learn the same role in the simulated environment.

Software

Agents

The Blackwood environment is populated by software

agents of the following types:

1.

Customer Agents: These

have been implemented and form the foundation of the economic simulation

(Farmers, Ranchers, Railroad Workers, Soldiers, Lumbermen, Transient Settlers,

Riverboat Workers, Teamsters, Miners and White Collar Townspeople, and several

others). These represent psychographic groups or clusters of consumers; Hooker

and Slator, 1996) and their shopping behaviors simulation demand.

2.

Merchant Agents: These are not currently

implemented but are intended to simulate the activity of agents who run

businesses in competition with human players. There are eight merchant roles to

be filled by players or merchant agents (Blacksmiths, Cartwrights,

Wheelwrights, Dry Goods Store Operators, Tailors, Wood Lot Operators, Stable

Operators, and Leather Makers)

3.

Employee Agents: These

agents see to the daily operation of retailing outlets and conduct the actual

transactions with the customer agents.

4.

Banker Agents: These

agents write loans depending on the player’s financial profile.

5.

Teamster Agents: These

agents deliver goods from the Riverboat landing and the Railroad depot, when

they are ordered by players.

Player

Roles

Players are assigned a role in the Merchant class. The

system arranges that plausible ratios are preserved so the game is not

populated with 100 blacksmiths but no tailors. Players are required to procure

food and fuel in order to run their households and keep their employee(s) warm

and fed. In addition, of course, players must run their businesses as

profitably as possible to succeed.

Neighborhoods

Neighborhoods include the Town Square neighborhood,

the Old Business District, the Middle/Working Class neighborhood, the New

Business District, the Wagon Train Staging Area, the Riverside neighborhood,

the North Shanty Town, South Shanty Town, the Government/Financial District,

the Wealthy neighborhood, the Lumber Town, the Western Outpost and the Fort

Wood Trading Post. Neighborhood populations change over time to simulate the

various ebbs and flows of the demographic landscape.

Products

Products are defined according to historical context

and the demand value for customer agents. This definition of products, in some

sense, is what drives the economic simulation. There are 9 product types, 8

matched with the merchant types listed above (blacksmithing products, for

example, like nails and horseshoes), plus groceries and supplies.

Suppliers

Wholesale suppliers are conceptually “back

east” and players orders goods through a catalog interface. Delivery is

made to the player’s shop by Teamster agents, described above.

Advertising

Advertising is accomplished through placing ads in the

local newspaper.

Blackwood as a

Class Project

As of January 2001, the Blackwood game was functional

and running continuously on a server located at NDSU. Software agents were

happily performing their duties as programmed. However, play of the game was

minimal. Blackwood was in need of further refinement.

The project had previously used students enrolled in

various classes to continue development of the Blackwood Project to some

success. Not only was the project enhanced by the student’s efforts, but

also the student’s were exposed to networking, role-playing and virtual

reality concepts.

The Spring Semester Class of NDSU’s course on

network topics was another such class. In order to further enhance the idea of

role-playing as a viable educational tool, the class was structured to emulate

a consulting team working on a common project: Blackwood. The structure of the

class was as follows: Project Managers, Scribes (to record progress), Server

Team (back-end processing), Java Team (front-end interface), HTML Team (web

site development), and Graphics Team (refine graphical components). Elections

were held for the lead positions in each area. Once the leaders were

inaugurated, a “draft” of the rest of the students was held to

determine their membership in a team. Students were chosen for a team based on

their wishes and qualifications as outlined in a resume they were required to

submit to the team.

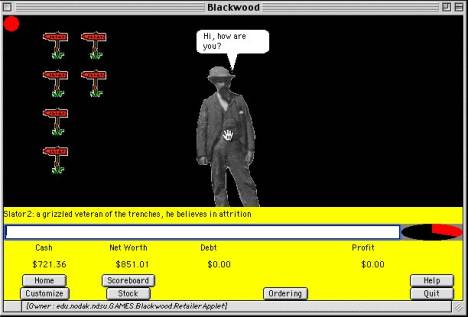

Figure 1: The first Blackwood inteface

Project

Preparation

As in any large consulting project, each team needed

to determine the present level of implementation and determine a course of

action. Reviews of the project progress commenced, brainstorming sessions were

held and eventually a list of tasks were outlined. In addition, as many of

these students were previously unfamiliar with the technologies required to

achieve their goals, exercises and benchmarks were assigned in order to provide

them with the knowledge and skills required to contribute in a significant way

to the project. These activities took roughly half of the semester (8 weeks).

The remaining 8 weeks of the semester was dedicated to achieving the goals

outlined in the task list.

Task

List

Once the rough task list was generated during the

brainstorming sessions, it became the responsibility of each group to further

refine these tasks, evaluate their viability, and establish a final, detailed

task list for their team. These

lists were consolidated into a master task list and posted on the ever-growing

BlackWood Project website, where any member of any group could log on to see

what each team was doing at any given time.

The task list then had to be translated into a series

of goals. To further complicate matters, dependencies existed within and

between teams. Eventually, Gantt charts for each group were created as well as

one overall Gantt chart listing all tasks, their estimated duration and a

completion goal. The tasks (goals) identified by this class are as follows:

HTML

Team

§

Construct a

“Progress Report and Evaluation” web site for use by the students

to report their progress and submit evaluations of fellow team members.

§

Develop the Blackwood

website to have a consistent look and feel with the Blackwood Game Java Applet.

§

Research and add content

to history pages on the Blackwood website that include background on Blackwood.

§

Develop a registration

page that forces players to register prior to playing the game, thereby

collecting demographic data on Blackwood players.

§

Develop a set of

instructional pages on the Blackwood website, providing a useful and concise

guide to new Blackwood players.

Graphics

Team

§

Work with HTML Team to

develop web site graphics as needed.

§

Work with Java Team to

develop interface graphics as needed.

§

General cleanup of

existing images. Some images did not look authentic or were badly sized.

§

Create store interior

graphics.

§

Create indoor and

outdoor scenes.

§

Create graphics for

products.

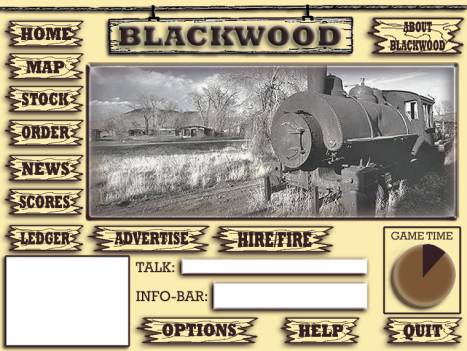

Java

Team

§

Rework Java interface to

have a consistent look and feel throughout. In addition, create an interface

that looks authentic to the Blackwood era.

§

Redo the login controls.

§

Continue adding

functionality to the ordering, hiring and inventory functions in the game.

§

Add functionality

allowing the player to customize their play options.

Figure 2: the second Blackwood interface

Server

Team

§

Work on timeline in

order to launch events when appropriate in history.

§

Work with Java group on

the reworking of the login controls.

§

Create a “Hall of

Fame” that saves a player’s progress when they have stopped playing.

§

Build stores that are

present in the original proposal but do not yet exist in Blackwood.

§

Repair errors in

existing routines.

§

Work on enhancements to

the routines involved with buying, selling and ordering products.

Progress

When the actual work of completing the tasks

commenced, the goals seemed lofty. The BlackWood interface was very crude and

was lacking in many areas. The

shops did not look like shops at all, merely black screens with red dots on

them to represent products. There

were no doors into each room, nor was there any detail in the shops or on the

streets. The images of the people

(the players) were all different sizes and lacked any sort of consistency. In short, the game had a good start,

but still had a long way to go.

The students in each team faced the daunting task of finding a way to

redesign the game into having a consistent and authentic 1800’s interface

and gaming environment.

The teams showed they were up to the challenge and

quickly began organizing themselves into subgroups. Each team worked independently, led by their team leaders.

However, the dependencies that were noticed during the preparation phase

started to create problems. One team was forced to wait for another team’s

product in order to begin work. This created stress and friction, not unlike a

“real” consulting team’s dynamics. Thankfully, these issues

were worked out in a professional and efficient manner and real progress was

made.

Most team leaders assigned small, achievable goals to

each team member or subgroup. This allowed teams to work in parallel and

produce results much more quickly. To date, all tasks are on schedule per the

Gantt chart and the class expects to complete all the tasks assigned by the end

of the semester! It would be interesting to measure the performance of this

class, working in a role-playing environment, to another class, working on the

same goals, structured in a “typical” fashion.

Progress

Reports and Evaluations

In order to track progress by each team member (not to

mention assign grades), each student was required to submit regular progress

reports via the web. These progress reports were designed to emulate reports

that would be submitted to a client during a large project implementation. Each

student was then required to evaluate 7 – 12 students based on their

progress reports. These evaluations not only reviewed the work generated by the

student, but also their ability to effectively communicate their long and short

term goals, describe the tasks that had been completed and present all of this

in a professional document.

Conclusion

The game of Blackwood is an immersive, role-playing

environment where players can have fun, while learning some valuable

“real-world” skills and knowledge. There is increasing evidence of

the value of this type of “active” learning. Further proof may just

be the actions of the Spring Semester 2001 CS345 class at North Dakota State

University. The students in this class were able to accomplish a wide range of

goals and apply these accomplishments to a tangible product that is usable by

the public, instead of the typical “practice” program that will

never be run once the instructor has graded it. But, possibly more valuable are

the skills these students learned by acting out a role in a project team.

Project teams are widely used in the Information Technology industry to

accomplish goals. The experiences of acting in these types of roles will serve

these students well in their future careers.

References

Curtis, P. (1997).

Not Just a Game: How LambdaMOO Came to Exist and What It Did to Get Back at Me.

in Cynthia Haynes and Jan Rune Holmevik, Editors: High Wired: On the Design,

Use, and Theory of Educational MOOs. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan

Press.

Duffy, T.M. Lowyck,

J. and Jonassen, D.H. (1983). Designing environments for constructive Learning.

New York: Springer-Verlag

Hill, Curt and Brian

M. Slator (1998) Virtual Lecture, Virtual Laboratory, or Virtual Lesson. In the

Proceedings of the Small College Computing Symposium (SCCS98). Fargo-Moorhead,

April. pp. 159-173.

Hooker, B. and Brian

M. Slator (1996). A Model of Consumer Decision Making for a Mud-based Game.

Submitted to the ITS’96 Workshop on Simulation-Based Learning Technology.

Montreal, June.

Reid , T Alex (1994)

Perspectives on computers in education: the promise, the pain, the prospect.

Active Learning. 1(1), Dec. CTI Support Service. Oxford, UK

Shute, V. J., &

Glaser, R. (1990). A large-scale evaluation of an intelligent discovery world:

Smithtown. Interactive Learning Environments 1(1), 51-77.

Slator, Brian M. and

Harold “Cliff” Chaput (1996). Learning by Learning Roles: a virtual

role-playing environment for tutoring. Proceedings of the Third International

Conference on Intelligent Tutoring Systems (ITS’96). Montreal: Springer-Verlag,

June 12-14, pp. 668-676. (Lecture Notes in Computer Science, edited by C.

Frasson, G. Gauthier, A. Lesgold).

Slator, B.M., Juell,

P., McClean, P., Saini-Eidukat, B., Schwert, D.P., White, A., & Hill, C.

(1999). Virtual Worlds for Education. Journal of Network and Computer

Applications, 22 (4), 161-174.

Acknowledgments

The NDSU Worldwide Web Instructional Committee (WWWIC)

research is currently supported by funding from the National Science Foundation

under grants DUE-9981094 and EIA-0086142, and from the Department of Education

under grant P116B000734.